An interesting thing happened to me last summer: I was plagiarised.

Basically, a post appeared on a political science blog belonging to a highly-regarded European university which was, apart from about two original paragraphs, a near word-for-word reproduction of an article I had written just a few weeks prior for the blog of the organisation I then worked for. The plagiarised post was published under the name of a real academic, though not someone I had heard of. The theft was laughably blatant: the sentences had been rearranged a little in some places (though not everywhere), and almost nothing had actually been reworded.2 Even the section heading I chose as an homage to Rosa Luxemburg was kept in place.

This was a novel experience for me. My writing has elicited strong positive and negative reactions from various people at various times, I have been the subject of minor far-right smear campaigns,3 and I have even passed my own work off as the work of others,4 but never before has someone wanted to claim that my work was theirs. Fascinating.

I did not discover the theft on my own; a colleague came across the blog post and shared it with the team.5

My first instinct was to be bemused and amused.

Even if I had been otherwise inclined to get angry, the repackaging job was so half-hearted and amateurish as to be comical. It was also, frankly, somewhat flattering to know that even a frankensteined version of my writing was apparently good enough to be published in this setting.

The bemusement had a similar genesis. Though the venue of the plagiarism was not formally academic – not a journal or conference, and certainly not peer reviewed – it was the blog of a university, and the person taking credit was a career academic. Given academia (nominally, theoretically) takes plagiarism very seriously, why risk the reputational damage on such a low-effort endeavour? It’s one thing when academics steal from their own students, when they may reason that no one will ever find the original; it is quite another to steal from something very recently published, which related to a small, specialised field – the practitioners of which number in the low dozens in Europe and all know each other.

So after I’d exhausted the “this is proof that I’ve made it as a writer” jokes, I became fixated on one question: how did this happen?

The seminal work on internet plagiarism was, of course, published 14 months ago by Hbomberguy. The four-hour video essay contains much valuable meditation on the psychology of and motivation behind plagiarism. It was on my mind during this episode. Still, it can be applied to my case only partially, I think. It is concerned chiefly with plagiarism in the realm of YouTube, and Hbomberguy’s thesis for why people plagiarise – because they crave validation and/or success but lack the skills to achieve it, and see those they crib from as unworthy of their respect anyway6 – felt to me like it failed to fully explain my experience.

In the case of plagiarism, as in all harmful behaviour, I am interested in knowing what the offending parties are thinking when they do it and how they justify their actions to themselves.

I find it very hard to imagine the process of copying and pasting someone else’s writing into your Word document7 and then trying to conceal it by way of editing. Even if you don’t view that behaviour as wrong, would you not be kind of embarrassed to debase yourself like that? Perhaps, as someone who really enjoys writing in almost any context, I am overestimating the pride people have in their own work, or underestimating their laziness. Perhaps I am imagining that people’s consciences are more vocal than they really are.

Still, we’re not talking about an undergrad ripping off an obscure journal article to finish an imminently-due assignment for a class they don’t care about, this is a case of someone who chose a career in academia publicly taking credit for someone else’s work.8

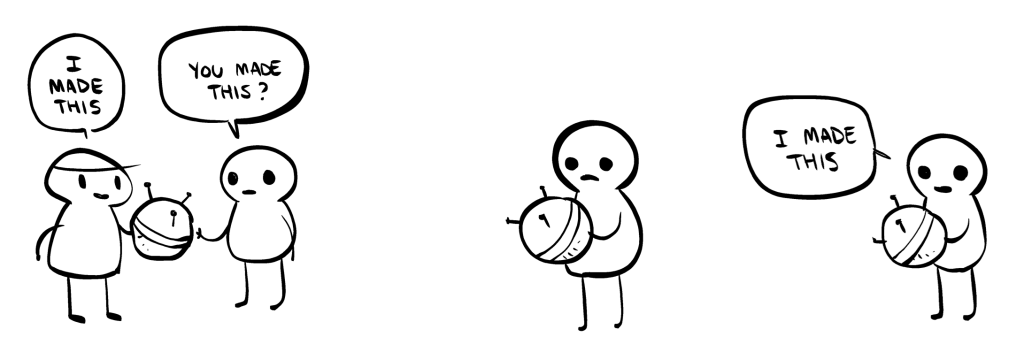

I don’t know about anyone else, but I have no interest in receiving credit or praise as such; I am interested only in receiving credit or praise for my work. Yes, I absolutely crave external validation – I’m only human – but only actual validation of me as a person, not the mere performance of it. I will feel validated only if the thing people are commenting on is actually the product of my labour and intellect and therefore a reflection of my abilities and character. I don’t just want to hear the words.

Also, does it not eat at you? With every positive comment, every time someone makes reference to what “you” wrote, do you not feel a twinge in your gut? Maybe it’s my deeply-rooted cultural Catholicism speaking, but I think that would bother me. Rather a lot, in fact. How can recognition you know to be hollow ever be remotely satisfying?

So is plagiarism a symptom of a person’s fundamental shallowness, an indication that they desperately want positive attention from others even when it reflects no labour or inner quality on their part? Maybe, but I don’t find that satisfying as an explanation. It brings me no closer to imagining what a plagiariser tells themselves as they do it.

I reached out directly to the editor of the blog that had published the plagiarised article. They took it down relatively quickly (though without publishing an acknowledgement, which I had requested), and said they could put the academic in contact for the purposes of a “formal apology”, if I wanted.9 I said yes – not because I really cared about being apologised to, but because I hoped in the process I might learn more about what had happened. I received the following:

My name is […] and I am the person responsible for the really serious situation that has occurred in the past few days.

I am grateful that you have accepted to share your email address with me, in order to receive my formal apology.

Going into the details of what happened would involve other people and I wish therefore skip details, which I also think are fundamentally irrelevant. My name was eventually on the post and I am therefore responsible. What matters here is that the piece was your intellectual property and the result of probably several hours of work. These things should simply not happen – or official and formal methods of quoting and referencing should be taken.

May I reassure that, in no way, I am unaware of what plagiarism entails. In no way, also, I take this not seriously.

I hope you could accept my formal apology. I understand if you do not wish to accept them.

There were two things that struck me about this email. The first was that though the subject line was “Formal Apology”, the body does not contain the words “I apologise”, “I’m sorry” or any synonyms anywhere. It twice references an apology that is presumed to exist somewhere else in the text, but it is nowhere to be found. The second was that it, if anything, significantly deepened the mystery over what precisely had transpired.10

Listen, clearly myself and this academic disagree on a number of things, but when you take credit for a bastardised reproduction of my work but simultaneously claim that you understand and abhor plagiarism, I really have to emphasise how much I do not think “details…are fundamentally irrelevant”.

I shared the email with some friends at the time, and theories were proffered as to what it might mean. Some thought perhaps the plagiarism had been done via a large language model (LLM), like ChatGPT. I think this is unlikely for several reasons: my article had only come out a few weeks before, and therefore probably hadn’t been crawled by most LLMs yet; and while admittedly my experience using such tools is limited, based on what I’ve read (and what I know about how neural networks function) I think very obviously and sloppily plagiarising a single source would be highly unusual behaviour for them – unless the user specifically asked.

The other popular theory, and one that seems most plausible to me, is that the phrases “involve other people” and “My name was eventually on the post” indicate that the writing of the article was farmed out to another person or persons – likely some combination of intern, research assistant, and student – and they plagiarised.

If true, this raises a whole host of new issues and questions.

Ghostwriting is a tricky one. In formal academic settings – college assignments, journal articles, reports, conferences etc – it is universally considered an ethical violation and/or academic fraud. But this wasn’t such a setting; it was a blog. The blog in question does not have a very detailed editorial policy, but does describe itself as an “academic blog” hosting “academic commentary and research”. I think it is reasonable, then, to say that work in that setting should be held to general principles of academic ethics, and that ghostwriting therefore constitutes not-insignificant misconduct. Furthermore, the blog stipulates that contributors must meet a certain standard of academic or professional expertise, a policy which would make no real sense if the pieces were not written by the nominal contributors.

In other words, if my work hadn’t been stolen, this would still have been a case of plagiarism. It would just be plagiarising the ghostwriters instead of me.

Yes, the ghostwriters probably agreed to it, but that isn’t an excuse for two reasons. First, plagiarism with consent is still plagiarism, given the existence of “self-plagiarism”. Even if these ghostwriters were perfectly happy with the arrangement, it would still be dishonest of the academic to take credit for their work.11

Second, there’s a really good chance these writers were unpaid interns, or underpaid grad students, or some other victims of the rampant problem of exploited casual academic labour.12 Such unfair work arrangements are maintained by the implication that there is no other way to a career in academia;13 thus the “agreement” was very likely extracted under conditions of significant power imbalance.

So, ironically, given the rather opaque email was nominally trying to protect them from my wrath, I don’t think that these unnamed writer(s) bear any blame. If someone else is already going to dishonestly claim credit for your work, I say you are welcome to take any and all shortcuts when doing that work, up to and including plagiarism. Someone was going to get plagiarised, so you might as well have that someone be me, instead of putting in enormous time and effort just to have it be you. Fuck the system, man, I’m on your side here.

It’s possible, of course, that I’ve missed some potential explanation for what really happened here, or my picture of the situation is not quite right. But the email I received quite clearly indicates that someone was working on the problematic article without being credited for it, and this is clearly problematic.

So the academic did not plagiarise me in the direct way I had imagined, but had nonetheless set out to commit plagiarism from the beginning. My article being stolen was an accident, caused when the proximate victim(s) of plagiarism decided to save themselves some work.14

So we return, then, to the question of what makes people plagiarise and how they justify it to themselves.

It’s notable that the academic’s “apology” email didn’t even gesture at the idea that their initial intention – putting their name on an article written by their intern or whoever – might be bad. If anything it did the opposite when it kind of implied that them taking “responsibility” for the final product was brave, or an act of leadership, or upholding some kind of principle. It wasn’t, of course; they weren’t shielding a subordinate from trouble, they were hiding the details of their own meta-plagiarism. And in so doing, they brought into focus the absurdity of the whole business: yes of course you should be “responsible” for the contents of an article which you say you wrote – you should have written the goddamn thing.

In other words, though they professed to be keenly aware of “what plagiarism entails”, I don’t think it ever crossed their mind that they were, in fact, engaged in plagiarism all along. And perhaps this is the very unsatisfying answer to our question: people justify plagiarism to themselves by finding a way to believe they’re not doing it.15

In this case, it was probably a matter of having the interns write 98% of it – because research assistants do background work all the time, that’s normal – editing it lightly, and then publishing it only under the your name, because, darn it, the blog has those pesky rules about contributors’ qualifications.

When it comes to professors stealing from their students, they’re probably thinking that of course there’s no harm in re-reading that student’s essay now that you’re writing on the same topic. Maybe you’ll just copy and paste in the specific way they phrased something, just to help you structure this paragraph. You’ll definitely go back and rephrase it later. And after all, they learned from you when they wrote that essay.

Other times you don’t even need to paste, you just happen to write something in precisely the same words as a source you read,16 and if asked about it later you’re sure it was a total accident. When you’re talking about non-textual media, like in Hbomberguy’s video, that kind of precise recreation (since actually copying-and-pasting isn’t possible) is even easier to explain away as “inspiration” that got out of hand.

And so on and so forth.

On the other hand, one’s sense of cognitive dissonance would need to be really well developed for some of these cases. When this academic was telling their Twitter followers about “My latest contribution to [blog]” (and tagging a bunch of accounts in the process), was it not on their mind that they had no idea where almost all the text came from?

I am a person who feels the need to prove themselves. I have a well-developed sense of intellectual insecurity. But as much as I may feel the need to impress those around me,17 my biggest critic is and always will be the voice inside my head. If I plagiarised and got away with it, that guy would still know the truth and he wouldn’t give me a minute’s peace. In other words, I need to impress the people around me, but I also need their impressions to be well-founded.

So when all is said and done, I still don’t get it.

Perhaps I can’t.

- I generally try to be diligent about accreditation anyway but now would really be the worst time to break that habit. ↩︎

- And at the risk of twisting the knife or appearing self congratulatory and/or snobbish, where there were edits, they all made the writing worse. I feel strongly that:

1. if you’re going to edit plagiarised material, you should do enough editing to go some way to disguising the theft, otherwise you’re just wasting your time, and

2. If anyone is going to edit my writing, I would rather it was to improve it.

They went 0 for 2 there. ↩︎ - Who can forget when a far-right account (widely believed to be operated by Gemma O’Doherty) compiled my old tweets into infographics. Apparently the fact that in 2018 I tweeted “Next time I hear a food product described as ‘made without any chemicals’ I’m going to commit mass murder. Feel free to use this tweet as evidence at my trial” was a sign of rampant violent extremism on the Irish left, or something. ↩︎

- Enough time has passed that I am now comfortable admitting that, as editor of Trinity News, I occasionally wrote small, print-only pieces for the Sport section under the name “Alan Smithee”. We didn’t have a Sport editor so when I had not organised myself to find enough contributing writers, I ended up writing a lot of the articles myself, and I thought it would look bad in print if the same byline appeared four or five times in the same two page spread. I don’t think anyone got the joke of the name at the time. ↩︎

- Again, we must scrupulously give credit where credit is due. ↩︎

- This latter part is interesting to consider in the context of those stories of academics stealing from their own students, isn’t it? For the record I think Hbomberguy’s theory is a very good one, just not universal. ↩︎

- I do not find it hard to imagine doing the same thing for code, of course. Back in my day that was how all software got made. We didn’t need some stupid AI to copy other people’s work for us; we had StackOverflow and we were happy with it. Kids these days, I swear. ↩︎

- Including sharing the plagiarised article on Twitter and LinkedIn multiple times – posts which were not deleted and can still be found. ↩︎

- I had been planning to make contact myself, and had prepared an email draft that began “Hello, my name is Jack Kennedy. I believe you’re familiar with my work.” Alas I never got to use it. ↩︎

- On reflection, a third notable thing is the language of the email. The style and grammar suggest it was written by someone who is less than fully proficient in English. This is not notable on its own, but having done some minor research on the academic in question, I know they are without a doubt fluent in English, including teaching and publishing in it. So that’s odd. ↩︎

- And I must emphasise how directly credit was taken, even aside from the byline. The academic’s posts on Twitter and LinkedIn said things like “I have written…”, “in my latest article for..” etc. ↩︎

- Yeah, it’s technically possible that this was someone selling their writing skills from a position of relative autonomy, like a professional ghostwriter penning a sports star’s autobiography, but such a person would presumably not sloppily steal from me because it would be bad for their career. People not being fairly treated or compensated have more incentive and less to lose by such shortcuts. Plus if they were enough of an actual subject expert to demand real money, why wouldn’t they cut out the middleman and just submit to the blog themselves? ↩︎

- That implication is, of course, often accurate. ↩︎

- Just to reiterate: they have my unconditional support in this, as do all workers who cut corners in their crappy jobs. ↩︎

- Unsatisfying perhaps, but also an answer I could probably have foreseen if I’d thought about it harder. But then how would I have structured this blog post? ↩︎

- Just as background, so you conveniently didn’t need to cite it. ↩︎

- And I’ll be the first to admit it’s a somewhat pathetic need. Let’s call a spade a spade. ↩︎